Skift Take

Luxury hotels should be able to drive higher rates if luxury becomes more about what you do than what you own.

Luxury hotel companies could flash a half-decent report card this year thanks to a post-pandemic surge in demand. But they could do better long-term if management teams sharpen their focus on opportunities to woo well-off consumers who increasingly care about experiences.

That was the view of Richard Clarke, a managing director at Bernstein Research, who presented “A Macro View on Travel’s Future” at Skift Global Forum East on December 14 in Dubai.

Clarke and his team analyzed data from the hotel benchmarking service STR. They concluded that luxury hotels ought to command higher rates in the future in light of the willingness of well-off consumers to spend on other types of luxury goods and services at high levels. If shoppers are willing to buy Gucci handbags and Cartier watches, why aren’t they paying premiums for luxury hotel rooms?

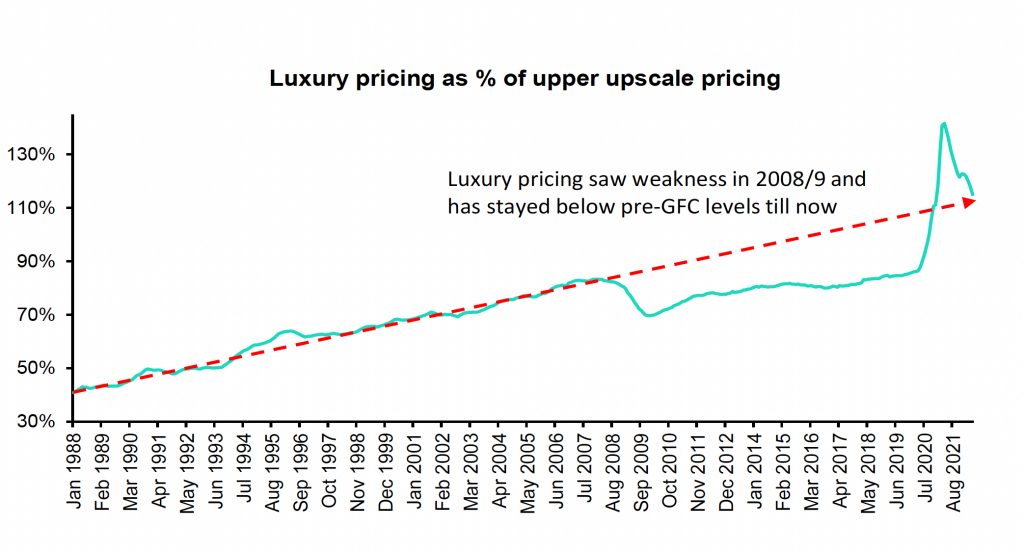

“You used to see an ever-growing premium of luxury hotels relative to upscale hotels,” Clarke said. “That stopped in 2009.”

In the past year, average rates for luxury hotels finally got back in line with the historical trend interrupted by the great financial crisis.

Closing the Luxury Gap

Valuations of other luxury products and services make five-star hotels look comparatively reasonable.

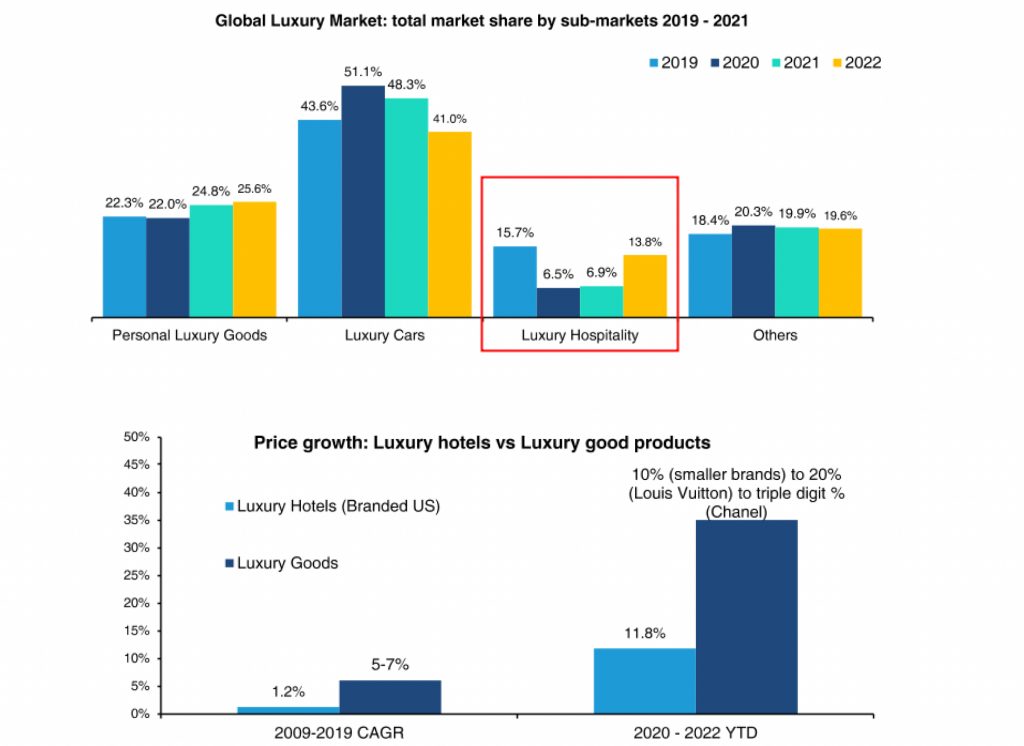

Data cited by Bernstein Research suggests that luxury hotel companies haven’t been grabbing growth and market share at the same pacing as makers of personal luxury goods and luxury cars.

“Even though every survey will tell you that luxury consumers want to spend more money on experiences, not less, we haven’t seen that catch-up come through in market share,” Clarke said. “If you look at luxury lodging as a percentage of the luxury market, you see there’s plenty of upsides to come.”

One sign of the coming shift came when LVMH in 2018 bought luxury hotelier Belmond for $2.6 billion including debt. The reigning leader of the luxury sector placed a bet that travelers would want more far-flung experiences in style.

Shift to Experiences

Clarke’s thesis dovetails with the arguments set out in the recent book Future Luxe: What’s Ahead for the Business of Luxury by Erwan Rambourg, an HSBC analyst.

Rambourg argues that sales of luxury goods before the pandemic were heavily powered by Chinese consumers traveling abroad. Demographic trends suggest there is still at least another decade of foreign shopping for bling ahead, given a rising middle and upper class in China.

Yet Rambourg also sees trends shifting in a direction that could favor luxury hotels.

“Luxury will be less about being ostentatious and more about feeling happy,” Rambourg writes.

Ancillaries as Profitable Key?

One challenge for hotels is how to do a better job of addressing the wants and desires of luxury consumers. Can hoteliers give the owners of $1,500 leather Christian Louboutin boots places and experiences where they can show those status symbols off? This is perhaps one of the questions to draw from the hit HBO series The White Lotus, where wealthy people show off their luxury clothes in the context of luxury properties in Hawaii and Sicily.

In the personal luxury goods business, accessories often deliver the fattest operating margins, with iconic brands such as Dior and Chanel commanding operating margins of 40 percent or more on their bags and shoes. The hotel industry equivalent may be upselling guests on ancillary services.

Hoteliers could look beyond rooms to focus on extra services they could glamorize in modest ways to justify margin-padded fees. Rambourg thinks of this as part of a broader “premiumization” of little indulgences. Recreational cannabis, wellness coaching, and private tastings could be possibilities for adding high-margin sparkle.

Reasons for Caution?

Some skeptics may worry that recessions in some markets will knock percentage points off luxury hotel performance in the next year or two. Inflation may also make luxury hotels more of a hard sell by raising the labor cost of providing high-touch service. Yet while worry is understandable, pessimism may be overdone.

“Luxury spenders are a separate breed,” Clarke said. “They continue to spend in recessions. … Their wealth has increased much faster than inflation.”

Another caveat to all the good vibes is that competition looms. Marriott, for example, said this month it plans to add more than 35 luxury hotels in 2023 to its nearly 500 luxury properties worldwide.

“The percentage of hotel room inventory that counts as luxury doubled from one percent to two percent over about the last 15 years,” Clarke noted.

If scarcity is a key ingredient in creating luxury, hoteliers must be careful that some destinations aren’t overbuilt. They also should take a cue from super-luxe Aman, which makes its individual suites, and campuses overall, feel secluded.

As a guiding principle, scarcity is associated with exclusivity and good taste, which is why the member’s club phenomenon illustrated by Soho House’s waitlist points to one model for hoteliers to consider. As Coco Chanel once supposedly said, “elegance is refusal.”

Luxury’s a good thing. But you can’t let everyone in on it.

Here’s Clarke’s full talk on a variety of reasons to be optimistic for travel’s future from Skift Global Forum East 2022 in Dubai:

Daily Lodging Report

Essential industry news for hospitality and lodging executives in North America and Asia-Pacific. Delivered daily to your inbox.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: Bernstein, hotel pricing, luxury

Photo credit: The Ritz-Carlton Paradise Valley, The Palmeraie in Arizona’s coveted Scottsdale area. Source: Marriott International.