The

Definitive

oral

history

of

online

travel

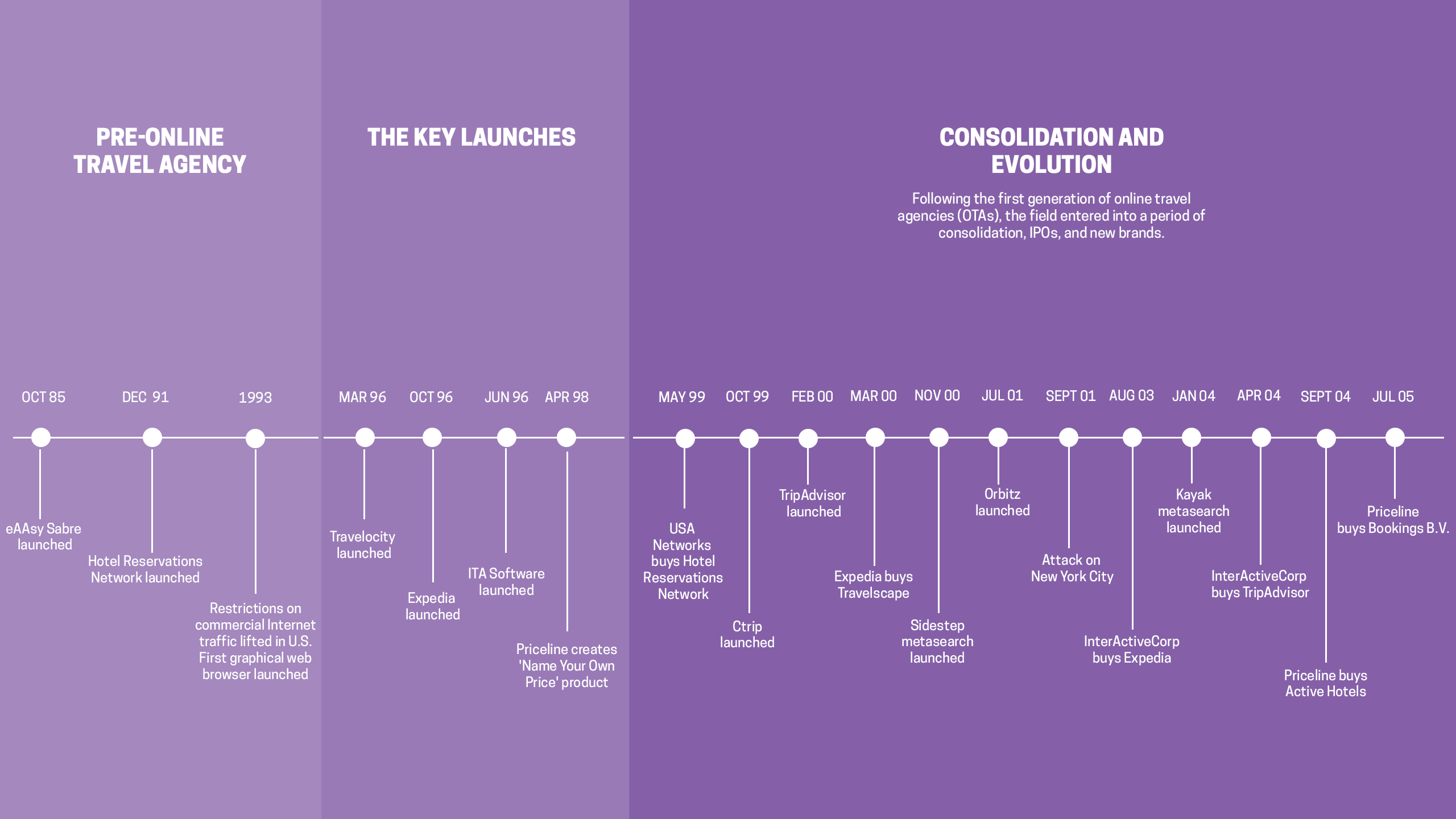

If you lived through the mid-1990s and early 2000s, and even if you are younger and newer to the travel industry, you are probably familiar with the headlines and highlights of those early years of online travel. Bob Diener and Dave Litman started selling hotels through a call center and built a powerhouse that became Hotels.com; American Airlines and its Sabre unit created Travelocity with Terry Jones at the helm; Jay Walker came up with a Name Your Own Price idea for selling discounted flights, hotels, mortgages, and new cars and launched Priceline.com; Microsoft's Rich Barton became the founder of Expedia; four major U.S. airlines decided to be very discriminating about which site would get access to their Web-only fares and enrolled as the founders of Orbitz.com, and Priceline's Glenn Fogel spotted European hotel distributor Bookings B.V., which everyone else seemed to be blind to, and acquired it.

On rare occasions over the years an enterprising journalist would uncover something about these companies and their trajectories that wasn't already in the public record but this was the exception rather than the rule. But that lack of insight into what was actually going on behind the scenes during those early years of online travel, from the early 1990s to 2005, ends right now with this, the Definitive Oral History of Online Travel.

As is the nature of an oral history, Skift provides you with insights into the dreams, challenges and acquisitions that battered and buttressed the early years of online travel and e-commerce as told through the occasionally contradictory recollections of more than two dozen founders, CEOs, and early employees. Their anecdotes and newsy, never-heard-before disclosures come interactively in the form of text, historic photos, audio clips, radio, and TV commercials and videos.

These interviews kicked off in back-to-back phone conversations with rivals Al Lenza, a founding Orbitz board member, and Rich Barton of Expedia in February of this year and concluded with a phone call to Hostelworld CEO Feargal Mooney in Dublin just last week. In between these four months of taking a time machine back into online travel yesteryear, among the more than two dozen individual oral histories recorded, Skift spoke with Hotels.com co-founder Bob Diener on Fifth Avenue outside the General Motors building in New York City; separately hosted former Sabre CEO Kathy Misunas, then-Priceline Group chairman Jeffery Boyd (now also interim CEO), and Kayak co-founder and CEO Steve Hafner in Skift's offices, and spoke with SideStep founder Brian Barth by phone as he drove his car after a travel tech conference in California.

One thing that came across in these overwhelmingly — and sometimes shockingly — candid interviews was these pioneers' emotional attachment to their work and play in the early days. For example, ITA Software co-founder and former CEO Jeremy Wertheimer talked to me effusively about the formation of ITA Software and the years leading up to it in the early 1990s because he was recalling and speaking about his youth, dreams, passions, and legacy. In that regard, several of the people interviewed called me back a few days later after their hour interview had been completed to chime in with some additional tidbits and anecdotes.

The stories they unveiled were personal, business-oriented and varied. While Expedia, for example, went online with Microsoft's marketing and financial muscle behind it and secured an office for 143 people down the road from Microsoft headquarters, Steve Kaufer and Langley Steinert's first TripAdvisor office was perched over Kosta's Pizza & Seafood in Needham, Massachusetts. On the personal front, Dara Khosrowshahi concedes he wasn't very good at the job of being Expedia Inc. CEO in the first few years and that his subordinate at the time, Steve Kaufer of TripAdvisor, taught Khosrowshahi that "speed takes care of a lot of mistakes."

Many of the founders and officials interviewed similarly felt free to be candid about developments that are now 10 to 20 years old. As Tim Poster, the founder of hotel-room seller Travelscape who went on to own the Golden Nugget casino in Las Vegas, summed things up about USA Interactive's aborted deal to acquire Travelscape: "This part wasn't public, but now who cares?"

At roughly 40,000 words, this oral history of the early years of online travel is the longest and perhaps most ambitious thing we've ever published. We think it is a compelling and tantalizing read as a way to not only relive the transformative years of online travel and e-commerce but also to take away lessons that have relevance today.

This oral history of the early years of online travel is extensive but not all-inclusive. There are big-name companies we didn't contact or a handful that declined to participate. As goes with the territory in the oral history that follows, we couldn't or didn't try to corroborate every fact or incident and sometimes 20-plus years after the fact, the people interviewed get hazy about the precise years things occurred and tell different versions of the same events. Some of the personalities, too, worry that they don't speak as neatly and grammatically off-the-cuff as they might write so take that into account if you come across run-on sentences or inarticulate phrasing.

There are many themes driving this oral history and lessons for the online travel employees and executives of today. One thing that stands out is that many of the pioneers who drove progress in online travel have known each other, have been doing deals with one another, and formed collaborative networks since the late 1990s. For example, Brad Gerstner, whose Altimeter Capital recently co-led a proxy fight that put former Orbitz Worldwide CEO Barney Harford on the United Airlines board, recalls taking a limo to current IAC and Expedia chairman Barry Diller's Hollywood home in 2001 to celebrate IAC's announced acquisition of Gerstner's NLG and Expedia. Among the attendees, according to Gerstner's recollection, were Diller, Khosrowshahi, Hotel Reservations Network co-founders Bob Diener and Dave Litman along with Expedia's Rich Barton and Barney Harford, who worked for Expedia at the time.

To illustrate the connections even further, in recent years, for example, Diller and Khosrowshahi's Expedia invested in Gerstner's Room 77, as did Zillow chairman and Expedia founder Rich Barton, who works alongside Zillow CEO Spencer Rascoff. In turn, Rascoff co-founded Hotwire, which was acquired by Diller's IAC and is part of Expedia Inc.; served as vice president of lodging at Expedia; was a board member of Gerstner's Room 77, and took a board post at TripAdvisor, which Diller's IAC acquired and spun off into Expedia Inc.

That's just one example of this travel industry version of six degrees of separation. Details about these relationships and anecdotes, as well as first-time revelations about the game-changing actions that shaped and still influence online travel history, are interwoven throughout this narrative.

Sit back, dig in and enjoy. — Dennis Schaal

Cast of Characters

(in alphabetical order)

Rich Barton Microsoft and Expedia

Jeffery Boyd Priceline Group

Geert-Jan Bruinsma Bookings.nl

Hugo Burge Cheapflights

Stephan Ekbergh Travelstart

Bob Diener Hotel Reservations Network and Hotels.com

Brad Gerstner National Leisure Group

Steve Hafner Orbitz and Kayak

Terry Jones American Airlines, Sabre and Travelocity

Jeff Katz American Airlines, Swissair and Orbitz

Stephen Kaufer TripAdvisor

Dara Khosrowshahi IAC and Expedia

Arthur Kosten Booking.com

Ellen Lee GetThere, Delta, and Orbitz

Al Lenza Northwest Airlines and Orbitz board

Kathy Misunas American Airlines and Sabre

Feargal Mooney Hostelworld

Michelle Peluso Site59 and Travelocity

Karl Peterson Texas Pacific Group and Hotwire

Tim Poster Travelscape

Bob Rosatto Decolar and Viajanet

Cheryl Rosner Kimpton Hotels, Hotels.com and Expedia

Jane Sun Ctrip

Alex Todres Decolar and Viajanet

Jay Walker Priceline.com

Jeremy Wertheimer ITA Software

Alex Zoghlin Orbitz and G2 SwitchWorks

Podcast

Dennis Schaal joins host Hannah Sampson — with audio clips from several interviews — to talk about the oral history, what surprised him about the project, and what innovations he thinks will shake up the industry next.

Listen closely for insight into what really went down in the decade that shaped the future in ways we may not yet understand.

Chapter 1: The First Wave

Kathy Misunas, former CEO of the Sabre Group

By the early 1980s, well more than a decade before the arrival of online travel agencies such as Travelocity, Preview Travel, Expedia, Priceline.com, and Hotel Reservations Network in the mid-to-late 1990s, American Airlines' Sabre unit had created a pre-Internet, direct-to-consumer booking tool for flights, hotels and cars called eAAsySabre. The awkward spelling of the product reflected American Airlines' parentage, which stuck "AA" anywhere it could. Throughout this oral history of the early days of online travel, the founders of companies such as Sabre-developed Travelocity, Hotel Reservations Network (later Hotels.com), Expedia, ITA Software, and Orbitz kept bringing up eAAsySabre as a precursor to, or inspiration for, their subsequent online travel sites and entrepreneurial efforts.

Sabre Discovers There May Be an Opportunity With Consumers

Kathy Misunas, former CEO of the Sabre Group and current consultant and advisor: eAAsySabre was not easy at all but it was easier than anything else that was available at the time. It was a request/reply-type system. We're in the early 1980s, a long time ago. Think back before any type of Internet. There were some private networks and some public networks like CompuServe or Prodigy, and Minitel in France. There were a few. Our product [eAAsySabre] allowed somebody who wanted to work through one of those networks to be able to answer questions. It would come back and say, 'Where do you want to go?' The person would type in, 'San Francisco.' It would say, 'When do you want to go?' They would type in, 'June 3' or whatever. 'How many people are going?' The same questions that an agent would ask.

Consumers could make reservations for flights, hotels and cars but airlines or travel agents had to do the ticketing. Sabre, which provided computerized reservation system [now known as global distribution system] services to travel agents, had to walk a fine line between this consumer-oriented eAAsySabre product and Sabre's travel agency customers. Travel agents resented the idea of consumers and airlines transacting directly and cutting them out of the selling and booking equation. It was a harbinger of the juggling Sabre would have to do for nearly two decades after launching Travelocity in 1996 and before selling it to Expedia Inc. in 2015.

Misunas: Way back then we had two different paths going on. We were totally supportive of the travel agents but we knew at some point, some day, consumers would be doing their own thing. We played with this, and I would get all sorts of questions from agents in seminars because they would hear about it and say, 'What are you doing here?' We'd say, 'How many people in the audience have heard about this? One, OK, so let's not worry about this. Let's move on.'

Then what happened was, on that platform, we decided that it didn't have to be request/reply. We would put up a template and it would be fill in the blank. Technology was starting to change. We could convince CompuServe and Prodigy to allow those types of templates. At the same time, travel agents were starting to really have a different type of automation on their own desktops.

Travel Weekly story announcing Misunas' Sabre appointment

IBM introduced a personal computer in 1981 and the first Macintosh computer showed up about three years later. eAAsySabre was evolving although the idea of an interactive Internet had yet to take hold.

Misunas: We weren't prescient enough back then to know that it was going to be the Internet in 1995. We knew that people were adapting a different way of purchasing and we felt, for travel, we had the tools. That's when we started saying, 'OK, let's put hotels in here. Let's put cars in here.' The things we did already had been available to travel agents. We started testing those. We started putting in other product. Then in the early 1990s, we created a department called Sabre Interactive. That's when we knew the Internet was going to become public in our lifetime.

Hotel Reservations Network Tries a New Way to Sell Hotels

Bob Diener, co-founder of Hotel Reservations Network

In 1991, as eAAsySabre was evolving, Bob Diener and David Litman decided to get into the hotel business and within a few years developed a business model that would revolutionize online hotel selling.

It was at a time when travel agencies were mostly interested in selling airline tickets.

Bob Diener, co-founder of Hotel Reservations Network, which became Hotels.com, and currently president of Getaroom.com: Hotel Reservations Network was our original company. We started it in 1991. Well, I was recently in the airline business. I was an airline consolidator. I sold my airline business. After about 6 months of sitting around the beach and being bored, my partner Dave Litman and I, we were talking about what we were going to do next. So we went down to Belize and spent a few days in a hut. Between scuba diving, talking about what we were going to do next and a lot of paper crunching, we came up with the hotel business.

We saw a great opportunity in the hotel business because the state of the industry then was that occupancy on average was about 60 percent. Hotels needed about 70 percent at the time to break even. We're in a recession, and we saw great opportunity to negotiate with hotels to offer, #1: consumers better rates and, #2: there was really no central source other than travel agents to find availabilities and rates on hotels.

Most travel agencies didn't want to book hotels because it wasn't profitable, and most people just picked up the phone at the time to book the hotel. At the time, the airlines were the ones that paid the big commissions, and hotels that actually paid the commissions paid 5 to 10 percent but you had to chase them.

This was still pre-Internet and online travel so Diener and Litman's Hotel Reservations Network started out taking consumer bookings over toll-free numbers but it was an uphill battle collecting commissions from hotels.

Diener: We learned after a very few months that it wasn't a very good business because very few hotels were actually paying us. We ended up spending 90 percent of our time as a collection agency and 10 percent of our time expanding the business. We brainstormed on how we were going to change this. It was our first major pivot. We came up with what we called the merchant model, where basically we approached hotels and said, 'It's much better if we get paid commission in advance.' Why don't we pay hotels a net rate and we'll sell the hotel at a gross rate. The customers will pay up-front and we could collect the commission in between.

Travelscape Vs. Hotel Reservations Network

Tim Poster, who founded Las Vegas Reservation Systems (Travelscape) and was former owner of the Golden Nugget and COO of Wynn Las Vegas: I started my company in 1990. We were just Las Vegas. I grew up in Las Vegas. Las Vegas back then was very, very different than it is now. It was very much of a who-you-knew sort of thing. We ended up doing a deal together, Diener and I, because he couldn't get into Vegas. We had Vegas kind of locked up. We had the merchant model. We did that. Again, it's a little bit difficult to say that we were the first because there were other people doing the merchant model, but not for just hotel rooms. Tour companies were doing it with airfare and big packages with show tickets and maybe even car rentals and Grand Canyon tours and things like that.

My idea was to just buy the rooms wholesale, get room blocks and go direct to the consumer because the margin was so much greater. I was able to do it because I was a local guy and I had connections with the hotels even though I was pretty young. We definitely were the first ones to do that in Las Vegas. As much respect as I had for Diener, I definitely did not want him coming into Vegas. I did what I could to keep him out.

This was in the early 1990s, maybe '93 or '94, something like that. I met Diener in Miami and he said that they had no interest in selling. I think they more or less told me that the company was worth way more than I probably could afford, although I don't remember any numbers being mentioned. What he was interested in was, of course, getting into Vegas. I said, 'Well, look, there's one way that you can get into Vegas. One way for sure you'll get into Vegas.'

By then I had a lot of juice with the hotels in Vegas because I was giving them so much business and the hotels weren't going to do anything to get sideways with me. I said, 'Look, if you really want to get into Vegas, I have the inventory and I can get more. What we can do is, I can basically give you blocks of rooms and I buy them from the hotels and I mark them up and you buy them from me.' He agreed. He said, 'OK.' That's what we did.

Diener: There were several problems with that [merchant] model. Number one, people we talked with about it said, 'Well, who's going to pay in advance? Who are you?' We realized if you give consumers a good deal, they will actually pay in advance. That was challenge number one. There was no pre-paid model. At the time, consumers went to the hotel and you paid at the hotel. The second issue was getting terms from hotels and having hotels bill us versus just having the consumer go and pay directly by credit card.

Hotel Reservations Network Signs Its First Merchant Model Contract

Diener personally visited the now-long-gone Dorset Hotel on W. 54th Street in Manhattan and it became the first hotel to submit to Diener and Litman's then-nouveau merchant model.

It is a business model that transformed online travel and the hotel industry. In July 1999, Barry Diller's USA Networks acquired Hotel Reservations Network, and in March 2003 bought Expedia.com, and the two merchant-model practitioners came to wield tremendous power over hotel distribution – much to the resentment of the hotel industry.

Diener: This was our first hotel and I actually went there personally and talked to the general manager and really pleaded with him to work with us. We were actually selling a lot of their rooms on a commission basis. He said, 'Bob, you have no references. You have no assets, but I'll tell you what: If you pay us weekly and promptly, we'll continue to give you terms.' That was our first hotel. Then we went to the next hotel and after months of working with the Dorset, we give the next hotel the Dorset as a reference. That blossomed and then all of a sudden we expanded to five other major cities and we're having thousands of other hotels giving us terms.

Diener said in 1995 he and Litman came to understand the potential of a new technology called the Internet.

Hotel Reservations Network Reluctantly Launches a Website in 1995

Diener: We had a friend of ours knock on the door. His name was Dave Rae. He came in and he showed us the technology. This was before Travelocity and Expedia. Most people had never heard of the Internet. There were really no sites for commerce. The Internet was not interactive at the time. The only way to access the Internet was through a phone connection. It was a very slow connection. You couldn't send something and get an instant response. You had to send something, they would receive it. Then you'd have to respond separately. It wasn't an interactive back and forth. We were very reluctant, mainly due to the speed and the fact that it was not interactive. But Dave Rae said, 'Let's make a deal. I'll build you the site. I'll pay for it and you just pay me a 10 percent commission.'

So we said 'fine, that sounds great.'

An early version of Hoteldiscounts.com, the precursor to Hotels.com

At the time you could register any domain for about $16. We went and bought the name Hoteldiscount.com and Hoteldiscounts.com and that was our first website. It was a shocking yellow color, similar to the color that Spirit Airlines is using on their website and planes right now. But it stood out. And it turns out that we launched the site in late 1995, early 1996. And in 1996 it was about five to six percent of our business. We were really impressed with it.

It was still non-interactive. It was very slow so someone would come in and look at the site and request a room, and then we would have to look at it, book it, and respond back to them. It could take hours before there's a completed transaction, but it was a great source of business. We said, 'This is great.' As far as I know, I believe it was the first hotel website. Terry Jones can tell you about this: Sabre had something at the time called eAAsySabre. It was very difficult to use. Prodigy and AOL were really the two main Internet sites that were out there at the time.

It could take hours before there was a completed transaction, but it was a great source of business.

We were so impressed with this that we went to Dave Rae and said, 'We want to buy the site from you.' He was busy with his gaming, which was doing well. He was more than happy to sell the site. So we bought the site. It was a minimal amount.

A Young Rich Barton Has a Surprise for Bill Gates in 1994

Rich Barton, Expedia founder and first CEO

It was 1994 and Rich Barton, who went on a couple of years later to found Expedia out of Microsoft, had transitioned from stints as a product manager for DOS 5 and DOS 6 and working on the Windows 95 team within Microsoft to its hot and sexy consumer division.

At Barton's first product review meeting in the big boardroom he was to present to Microsoft co-founder and CEO Bill Gates; executive vice president of worldwide sales and support Steven Ballmer, and group vice president of applications and content Nathan Myhrvold.

But Barton, 27 at the time, had a surprise in store for the trio because he was going to tell Gates that his pet project in travel – to develop an Encarta-style and CD-ROM-based travel guidebook – was a dumb idea.

Rich Barton, Expedia founder and its first CEO; currently executive chairman of Zillow and a venture partner at Benchmark: I didn't say it that way, but I said, 'I just think this is small.' The whole book-publishing business is maybe a $100 million a year [opportunity] and if we got 100 percent of the business that didn't matter much to Microsoft. But in the course of that project and building the business plan, I did discover eAAsySabre because I was a geek using online services like CompuServe, Prodigy, and the like. This was before the graphical Web.

I discovered this thing called eAAsySabre, which was a command-line program with basically the old DOS interface. It was intended to be used by travel agents who weren't in their offices. If they were home and had to field a call from their clients and they had to deal with making changes to a trip. It was their online access to their Sabre reservations where they could look, shop or modify, etc. Sabre decided to make this user interface, this little program, available to the general public. They made it available to people like me who were using CompuServe and Prodigy.

I looked at that and I thought, 'Oh wow, this is cool. This is really cool.' Consumers don't want to have to pick up the phone to talk to a travel agent just to understand what the schedules and availabilities are. They don't want to have to pick up the phone to get pricing. They want to actually do it themselves.

I was one of those guys who was a frustrated business traveler myself, and I remember being on the phone with the corporate travel agent at Microsoft and wanting to jump through the phone, turn the computer towards me and do it myself. I could hear the click, click of the keys that the corporate travel agent was using so I knew she was using something on a computer.

Bill Gates and his colleagues in the Microsoft boardroom saw eAAsySabre and bought into Barton's vision. But what also enticed them is they saw a business opportunity in trying to replace a lot of those big-box mainframe computers that were crunching data at companies such as Sabre and major airlines and replacing them with PCs running Microsoft Windows NT software.

Barton: I demoed this for Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer and Nathan Myhrvold. I can't remember who else was in the room, and said to them, 'Look, I think we could do a Windows version of this and really blow the doors off of a travel product.' It didn't just help people with travel guide information, but actually helped people make and take and plan and purchase trips.

They loved it. They were familiar with Sabre, and they knew the travel industry was one of the biggest industrial consumers of mainframes for IBM and DEC [Digital Equipment Corp.]. It was our mission at Microsoft at the time to rebuild everything that a mainframe could do on a modern PC by Windows NT and other modern software and hardware products, so I posited that we could actually rebuild the reservations systems on Windows NT and build a better mousetrap. They got really excited about that for obvious reasons. We ended up doing that, rebuilding the whole faring system.

Microsoft's Bill Gates and American Airlines' Bob Crandall Talk Joint Venture

Terrell Jones, former chief information officer, Sabre; founder and first CEO of Travelocity

Gates indeed was all in and along the way he approached then-chairman and CEO of American Airlines Robert Crandall about the idea of Microsoft and Sabre developing an online travel site together.

Terrell Jones, former chief information officer, Sabre; founder and first CEO of Travelocity; former chairman of Kayak, and currently executive chairman, WayBlazer: There's another part of this story that Rich [Barton] may have told you that, during this period of time, Bill Gates visited major accounts with his sales person. He would come at least once a year. We were a big Microsoft shop, and he was interested in travel. He proposed to Bob Crandall that we do a travel site together, and that Microsoft would do the front end and Sabre would do the back end because they were good at UI and we were good at reservations. Bill and Crandall talked about the idea of a joint venture online service. eAAsySabre was already operating. Kathy Misunas and I spent a lot of time with Ballmer trying to negotiate that deal. Steve Zollo, who was running eAAsySabre, says he showed it and our Internet idea, not yet named Travelocity, to Rich. Microsoft eventually decided to go their own way as did Sabre, and Travelocity was born and later Expedia. A deal was not possible. We both wanted to drive the car.

Barton: That's the first I've heard of Terry's story. Or at least that I can remember.

My pitch to Bill [Gates] and Steve [Ballmer] was in the context of an Encarta CD-ROM for travel and I was telling them we shouldn't do it. My eAAsySabre demo was a small part of the meeting. I don't recall if Gates had already seen eAAsySabre, but I'd guess he had.

After we got the green light, Greg Slyngstad and I spent quality time with Terry and American Air and Sabre folks trying to do a deal for connectivity or co-development. I don't recall Bill and Steve being involved at all, but it's possible they chatted with Crandall. They only cared because AA bought so much mainframe hardware-slash-software, and Microsoft wanted to get PCs and Windows NT in there.

It was a losing battle. Terry didn't want to do a deal with Greg and me. He was pretty cocky and comfortable that Sabre/AA were in the driver's seat and didn't want to invite Microsoft into the party.

I wouldn't have either.

AA people were very dismissive of me, too. So, we spent a ton of time with Galileo, Amadeus, and Worldspan, as well. Ultimately, we partnered with Worldspan for a global distribution system connectivity, and away we went. GDSs were all functionally equivalent from our perspective. One of the early R&D projects for us that was so cool was Best Fare Search, which rewrote airline pricing on a modern tech platform. This was a game-changer for Expedia as it was something the GDSs didn't want to have happen and therefore didn't do.

After getting approval from Gates around 1994, Barton and his team started building a booking service but it wasn't going to be a website at first.

Barton: I thought of those guys [Gates and Ballmer] as my venture capitalists. I pitched them on starting it on the outside of Microsoft because I figured it was going to be a travel business, not a software business, and that's how we got going. That was in 1994, before Mosaic and Netscape. Netscape and Mosaic happened pretty shortly thereafter. We originally started building it for what was called MOS [Microsoft Online Services], which was a competitor to AOL, intended to be, and it was a proprietary online service. When Netscape and Mosaic happened, I and my team knew right away that these proprietary online services were not going to survive, so we pivoted in the middle of the development project, even before we released it, to the graphical Web.

[The team included] the names that you'd know who have stayed around such as David Beitel, who ended up being the CTO of Expedia. He was one of the first engineers we hired. He is now the CTO of Zillow. Robert Hohman was the development manager and engineering manager. He's now the co-founder and CEO of Glassdoor. Byron Bishop [became a senior vice president at Expedia] and Greg Slyngstad was the first GM of the project. Greg was there. Simon Breakwell was one of the first guys that we hired from the industry, and then Erik Blachford, who later became CEO of Expedia after I left.

The idea was to build the largest seller of travel in the world. That's kind of how I pitched it. They wanted me to do that one step at a time, of course, and we went out and we got a deal with Worldspan so we were able to access air, car, hotel in version one. It wasn't pretty, but in version one we shipped it on the Web in 1996, and we were in business. We weren't making much money, but it had caught on.

I mean nothing in Web 1.0 was all that pretty. A lot of clutter, a lot of design hangover from apps and multimedia CD-ROMs and desktop apps. It was like a lot of content stuff that turned out not to be that important. It was really slow. I don't know what the baud speeds were at that time.

We were transactional right from the start. We actually licensed a bunch of travel content as well, so we did have a bunch of travel guide information that we put up as well.

Expedia was not the first to make it to the public Web. Travelocity beat us by probably a year. Travelocity was out in front, and when we went public, as I recall, Travelocity was probably twice the size in gross bookings as Expedia was. I maybe misremembering a little bit, but that's probably about correct. Preview Travel was number three. Preview Travel, they were the AOL partner. The apps, if you will, the vertical destination sites to all these travel brands, they all had to have a Big Brother portal. Travelocity's was Yahoo, Expedia's was MSN, and Preview Travel's was AOL.

Travelocity Gets Born Within American Airlines and Sabre

Terry Jones founded Travelocity within American Airlines' Sabre division in 1996 but its roots go back to eAAsySabre a decade earlier.

Jones: I was at Sabre, and you need to go back even farther than that, probably 10 years earlier, or maybe eight years earlier. Sabre, at the behest of Max Hopper, who was our CIO, the visionary guy at Sabre, really, thought that this online thing is going to be big. We should put Sabre on AOL and other networks like it. You may remember there was a product called eAAsySabre. It was fairly primitive, but it was on AOL and CompuServe and Prodigy and several other networks.

An early Travelocity radio advertisement

One of the issues with it was the user interface, of course, had to reflect the design of the host, so AOL and CompuServe thought that they knew all about travel. So they kind of forced us into their design, but it was successful and it had hundreds of thousands of users. Now you could make a reservation, but that reservation was then automatically sent to a travel agent and you picked up your ticket from them. For an an airline ticket and for hotels and cars. TWA had a product, as well, called something like Travel Shopper.

I've been deposed on this many times because there are all kind of patent disputes about that because everybody says they invented online travel and, frankly, they didn't. So that had been around for about eight years, and what happened was eventually the travel agents woke up to the fact that long-term this thing was going to be a competitor. They went to Sabre sales and said, 'You guys need to kill this thing.'

Everybody says they invented online travel and, frankly, they didn't.

Instead of that, they gave it to me because I was running Sabre computer operations. They said, 'Why don't we put it over there?' I'd run it [eAAsySabre] during part of my career before, I had been a travel agent, and they said, 'Let's just get it out of Sabre.' Let me back up. I actually asked, when I was running it maybe four or five years before, 'Why isn't this thing on the Internet?' Because we found that we had customers coming to us from the Internet via CompuServe. At the time, we were pretty aggressive about getting it on more and more networks, and so they looked at it. At that time, the Internet was still under government regulation and you couldn't have commerce on the Internet.

Microsoft-Sabre Combination Could Have Been Big

Talks with Microsoft hadn't gone anywhere because each wanted control of the online travel site.

Jones: No question that Rich Barton drove him Gates to do their own thing. Microsoft had long discussions with us. I believe they were in good faith. You know, I mean I wasn't happy about it. I wanted to do our own things but we had our marching orders from our boss to go do it. Max Hopper, I think, was still there, who was the CIO, and Kathy Misunas. Maybe Hopper left, the boss was Crandall, and Kathy was running Sabre. So, he said, 'These guys are really smart about this stuff.' No question, Microsoft with their coverage, particularly at that time, they owned every PC, so it was powerful. It could've been a power combination, but it didn't work.

Terry Jones, right, speaking at the Travelocity launch party in New York City alongside Worldview president Neal Checkoway

I go to this meeting in 1995 and they say, 'We're going to talk about putting this thing on the Internet and we're going to partner with another company.' We negotiated with this company, Worldview Systems. This was a content company. They had lots of destination content, and, at the time, we didn't know whether booking or content would be big. We did a joint venture with this company, we called it Travelocity. I think one of us owned the name and one of us owned the URL, so it was sort of a Mexican standoff. There were four buttons on the home page, and two went to them and two went to us.

Airlines Try Doing It, Too

Al Lenza, founding board member of Orbitz

Al Lenza, former vice president, distribution and e-commerce for Northwest Airlines and founding board member of Orbitz: Early '95 is when the noise started. Right around this time, the Expedia guys came over, early '95, to talk about their vision to have an online travel agent. It was not just Rich Barton. It was another guy, Greg Slyngstad, I believe was his name. The airlines would save on commission because they would be interested in only five percent commission. Then they were just trying to position themselves as, 'We're good for you. We're good for the industry. We're going to be good for consumers, and we're going to give Travelocity competition, which is owned by a GDS, and we're independent.

Actually, Expedia gave us the idea to reduce commissions to five percent for all online travel sites and to do so early when they were small. We did that in the middle of '95. Traditional commissions were starting to come down. I think January '95 was the Delta cap, the $50 cap, the first hit. Our initiative to reduce online sites didn't really get much attention.

You had the kiosks starting. You had commissions being cut. Online OTAs. All these things were happening. The e-ticket was the enabler for e-commerce. There's just no doubt, without e-ticket, e-commerce would not have flourished, so that was the enabler, and it was comical. I don't know if you remember, but there were a million skeptics in our airline and in the industry, saying 'Nobody will ever go to an airport without a paper ticket.'

I don't know how many times I told the story about if you lock your briefcase in your trunk and you're stuck and your paper ticket is in there, you don't ever have to worry about that again. We spent more time selling internally the value of this and the potential than we did externally.

I don't know if you remember, but there were a million skeptics in our airline and in the industry, saying 'Nobody will ever go to an airport without a paper ticket.'

The external adoption was amazing. There were all these writers saying 'Always have a paper ticket because you can go to another airline faster, and you're trapped if you don't have a paper ticket.' It was just the stories that just kept being spread for people to fear having this. It was amazing. We implemented paper-ticket fees. That took 100 percent in no time.

We could do anything on our website and not have to do it anywhere else. That was how the word got out about CyberSavers. All of a sudden, the word kind of spread that if you shopped online that you get a better deal. Whether it was fact or not, in some cases and not, customers believed it. That's what brought the huge increase in volume in the early years. I remember getting complaints that this was unfair to the elderly and to the people who were technically challenged, that it was just not fair. In socialist Minnesota, it was a big thing about that it wasn't fair, and it wasn't equal.

It reminds me of the way people talk about Uber now versus taxis, that it's not fair. They're playing by different rules.

Jay Walker Searches for the Price Line in Various Industries, Including Travel

Jay Walker, founder of Priceline

Jay Walker, Priceline.com founder and currently chairman of Walker Digital and chairman and CEO of Upside: The idea emerged because we were looking to solve a problem. I ran a private an R&D lab called Walker Digital, and Walker Digital specifically worked on solving problems that we felt would be completely changed in what we saw was an upcoming digital age. We said, 'Look, in a world where digital tools and online networks existed, problems that in the past had been really impossible to deal with would be reinvented. Solutions would be reinvented because the world was about to change.'

The problem we were working on was how can a seller of perishable inventory discount their product to clear the market without disrupting the retail price for their own product? In other words, how do you have a sale and at the same time not hurt your regular sales, your regular customers. It was good for any perishable products. The question is if you had inventory that was perishing, networks would allow you to advertise that inventory in a unique and discreet ways. We knew that was coming but the problem was discounting it would only have disrupted your old retail prices.

So that and hence the name of the company is "Priceline" because there is a line which is the current market price for your product, the price line and you can't go below that line without destroying your own retail prices. Nobody is paying at retail if you're having a sale. That was the problem we were trying to solve.

One of the industries that we worked on to solve the problem in was the travel space because we knew that online travel marketing was very much how travel agents sold the business. And we knew that if you could create a solution to the problem in travel, there was an extraordinary amount of perishable inventory. At that time when we started, the airlines were flying about two million empty seats a day. There were many more airlines and the industry load factor was probably around 61 or 62 percent, unlike the 87 percent is today. The airlines were flying a lot of empty seats around, which meant there was a lot of perishable inventory but at the same time we knew there was a fair number of people who would fly if they could get the price they wanted. Those people were browsing, they were sitting on the couch at home or they were using alternate forms of transportation like the bus or whatever. So, effectively, there was a capacity to expand the airline marketplace if you can figure out how to sell to those people, how to capture that demand.

So we began working on the idea of a demand collection system. How would you collect demand for people who wanted to fly and were willing to fly, but at the same time were not getting this right price? That's where we had the insight to say, hey, if they told us the price they were willing to pay and secured it with a credit card, we would know that the unit of demand was indeed a real customer, not some fake customer, right? The only question was how do we collect demand that airlines would want to fill and that solution was to create a new product which was a product that said, look, you're going to have to agree as a leisure customer to fly anytime of the day on any major airline with up to one stop or connection on a non-refundable, non-changeable ticket. If you're agreeing to all those things, then guess what, the airline knew that you really were a leisure customer.

On that basis we said to the airlines, look, we have a new product, this super-leisure product. We have a new way to collect demand for the product and we're going to use this new-fangled thing called the internet and we're going to let the customer price the product so that will allow you the airline to see the demand curve all the way below the price line.

American Airlines' Bob Crandall to Walker: 'We Don't Like You'

Walker: The reaction from the airlines was very negative. So, the airlines basically said, 'We don't like you; we don't like travel agents; we don't like anybody who wants to sell our products. We don't believe that there is such a thing as super-leisure customers. We believe that people prefer our brand over every other brand. Our customers want our brand so we don't believe there's anybody really out there willing to fly any airline at anytime of the day. We don't agree that your product has validity, we don't agree that your market has validity, and we don't like you.

'Well,' we said, 'That's all very well and good but we're going to have a lot of customers who are willing to give us demand. We're going to come back here with a big, thick book of demand that's going to perish every day. And, at some point, you're going to say that you'd have rather had those customers than simply tell us how this doesn't exist.' That's a typical innovative problem: data shows up in an established corporation and the established corporations typically say, 'Well this isn't any good. If it was, our people on third floor would have thought of this already.'

I went down to go see Bob Crandall at American Airlines [before the launch of Priceline.com] and Bob, as you probably know, was a legend in the airline industry and was a tough, smart, bare knuckles airline guy, and I went in because his people had said, 'You know, there's this guy you need to meet. He has invented a way to use the Internet that could actually help us, Bob.'

Bob hated the Internet. He said, 'Alright if I got to see the guy, I'll see the guy.' I went down to the boardroom at American Airlines in Dallas, Texas. The boardroom at American Airlines has got, like, its own ZIP code, it's so damn big. It's like a giant room. Here I come in with two of my guys, and Bob Crandall comes in and goes, 'I hear you've got something that I might like. I doubt it, but show it to me, OK.' I said, 'Fine.'

I lay out the business and I lay out the concept and I said to Bob, 'Look, here's how the product's going to work. You got to have to agree to fly any airline except you'll be able to tell us one airline you don't want to fly. You've got to fly any airline but you get to pick one that you specifically don't want to fly.' Because I knew that most people had one airline they just didn't want to go on.

Crandall interrupted me and he said, 'Jay I hate that. I hate the fact that they can eliminate one airline.' I go, 'Bob, why do you hate that? You're American. They're not going to put an X next to American, they are going to put an X to somebody on the airline they don't like, some little small major at the time.' I said, 'Not American.'

He goes, 'You don't know the airline industry. You hate the airline you fly the most.'

He said, 'Jay, here is the story: One out of every seven trips in the [same] airline is a service failure. It's not our fault: weather, mechanical, problems with the airport gates, one out of every seven trips is a failure. Which means if you fly me regularly, guess what? You have experienced more failures, whereas when you try my competitor only once in a while, you get on his flight, it runs perfectly and you say, 'Why when I get on the other guy the flight is perfect and when I get on with you, Bob, your airline always breaks?'

I never forgot it: you hate the airline you fly the most. So I changed the product. I said, 'Fine I will commit you will not be able to eliminate an airline. You will fly any airline, just fly any major airline, it doesn't matter which one, you can pick one, OK. He looked at me and he said, 'Jay, let me just be perfectly clear. We would be better off if you were hit by a truck.'

Then I said, 'You're speaking metaphorically, right? You are not taking it personally are you?' He says, 'You know, it's nothing personal Jay. The Internet is the worst thing that could ever happen to the airline industry. It's going to allow for total transparency on our prices, it's going to allow the stupidest customer to control the pricing to the consumer when we can't even control it to the travel agents let alone to the consumer. It's going to upend this industry in a way that we will not be better off. So therefore, OK, we don't want you to succeed.'

He looked at me and he said, 'Jay, let me just be perfectly clear. We would be better off if you were hit by a truck.'

And I said, 'Bob, you can hit me with a truck. The Internet isn't going away. It's coming.' He goes, 'We will see, Jay. Usually it's just a handful of people that if they don't make it happen, it doesn't happen and you're one of those people.' I never forgot that – you hate the airline you fly the most – and American will be better off if I were hit by that truck.

The meeting ended and he said, 'We'll think about it, but don't hold your breath.' I suspect that the lack of cooperation in the airline industry the day before we launched might have had something to do with good old Bob. It's a real airline story, and I don't hold any ill will. I love the guys at American. They eventually did a lot of business with us. They're great people. I never took any of it personally. You know, the airline industry is a tough business. They hadn't made profits until the last year or so in its whole history on a cumulative basis, so anybody who think that they can run an airline go try. It's really hard.

Airlines Ditch Priceline the Day Before Launch, Except for TWA

Walker: I don't want to name names for a variety of reasons but they all pulled out the day before we launched. On the exact same day, they all decided that, 'maybe we don't want this to exist.'

That was a fun story.

The day before we launched. No, they didn't test it. They might have spoken with one another but that would be certainly against the law, so they probably didn't do that. That would be wrong. But we did get some very strange phone calls the day before we launched the business. 'You know, we told you we were going to do this but thanks so much.' The day before we launched, they all pulled out except for one airline [that] didn't pull out.

TWA didn't pull out. I think somebody forgot to make a call. That's exactly what most likely happened. We launched the business with our advertising and promotion. And, we told consumers if you're a leisure traveler and you're willing to be super flexible, we've got a new way for you to save money and the truth is the airlines are eventually going to lock in. It doesn't cost you anything to fly. You go on this new-fangled Internet, tell us the price you're willing to pay, and we'll come back to you in just a few minutes and give you a yes or no answer as to whether or not there's any airline willing to give you a seat at that price.

The UK Landscape and Cheapflights' Early Ambitions

Hugo Burge, former CEO of Cheapflights Media, co-founder Howzat Partners and currently CEO of the Momondo Group: In the UK, the landscape was very dominated by traditional travel agents, and also charter flights and charter packages. Also, with a company, which I don't think you've ever heard of called Teletext, which was a television data service that painfully rolled through the pages every few seconds. It was very hard to navigate. It was a monopoly at the time.

This was throughout the '90s. This was something that was prevalent. If somebody was looking for cheap flights, a lot of people would filter through Teletext or even through the deals pages of the travel adverts in the back of the newspapers. It was also a world in which things were beginning to be shaken up. Low-cost airlines were beginning to shake up the landscape and starting to seize the initiative from the charter airline. Ryanair and easyJet: Those were the two pioneers and later British Airways launched it's own one with Go. What was interesting was they started off bypassing the travel agents. At that point, it was pretty radical to bypass the travel agents because all consumers would book through the discounters or High Street stores or telephone numbers in the back of the newspapers. Initially it was radical enough to book on the telephone.

Then, of course, the Web started. The traditional companies like Thomas Cook, Thomson, and Airtours, and some of the bigger names of High Street like Trailfinder and Flight Centre didn't really seize the initiative on the Web. It was interesting, the Web initiative was seized primarily by a handful of airlines, the low-cost airlines. I think Flight Bookers, which with a consolidator, was one of the first to seize the initiative and launched the eBookers brand. It eventually got big and then was purchased by Orbitz, as we know, later.

But the early players and the early entrants into the online sector were really a handful of British companies, but Expedia was one of the first. I think in October '96 – it actually coincided with the launch of Cheapflights – so it's interesting that we know the story of Expedia born within Microsoft and funded to the tune of several hundred million dollars to get going. They were launched in the U.S. in October '96, but in the UK they followed fairly shortly after, I recall. But Cheapflights was at the right place at the right time. It was founded by a travel journalist John Hatt, who had been travel editor of Harpers and Queen for 10 years. And his very simple idea was to make finding cheap flights simpler. His idea was to make cheap flights advertising more logical and simpler by organizing deals by destination.

Cheapflights started as a listing service for flight deals from consolidators, from people who had websites, but predominantly people who had telephone numbers so it was kind of a Teletext killer in many ways. Because Teletext was a non-user-friendly source of cheap flights deals, and Cheapflights knew [it could succeed] in terms of being user-friendly and offering a great range of deals in an easy format.

John had a goal of transparency and aggregation from a very early stage. He felt that by not selling and by aggregating all the different suppliers and sellers of products that he could offer a more interesting and better product. And that was at the heart of his vision, simply buying cheap flights.

I think he loved the idea that [Cheapflights] did what it said on the tin. In fact, another anecdote which I find quite amusing – as long as it comes across right – is that John had always used to say: 'Cheapflights is an amazing name. It's like the naked lady of the travel industry. It's highly attractive, people know what it does, and people love it. People love Cheapflights.' He was a great advocate of that and it was really his personality and drive that really got the initial website going, and the vision.

Booking.com Traces Its Roots to a Recently Graduated University Student in 1996

Geert-Jan Bruinsma founded Booking.com's predecessor company, Bookings.nl in November 1996 a few months after graduating Universiteit Twente in the Netherlands and discovering the Internet. Bruinsma sold Bookings.nl to Bookings portal in 2003, roughly a year after IAC's Expedia unit had done its due diligence and decided – in what might be viewed as an historic misstep – not to acquire Bookings.nl. The Priceline Group acquired it in 2005, combined it with Active Hotels, and rebranded it as Booking.com.

Geert-Jan Bruinsma, Bookings.nl founder

Geert-Jan Bruinsma, who founded Bookings.nl and currently works on business development at Booking.com: I got the idea in August '96. It was after I graduated from university. In my final year of university, I got in contact with the Internet and I found it really interesting. And I always wanted to start my own business after university. At the end, I decided it had to be something with the Internet. I had no idea what. Then, during a dinner with friends, the idea of hotel reservations came up.

In the Netherlands there was a national reservation center. And you could call them and they had contracts with many hotels and so you could actually call them to make a reservation. It was a semi-private business. It was part of a public organization, it was the Netherlands Tourism Board but they put this into a private section of it. I think most common was just call the hotel directly. Get a phone number from a phone book or get the phone number from a travel guide if you want to go to Paris. Everyone knew that people in Paris don't speak English so you had to speak a couple words of French to make a reservation. It was always a hard time, especially the cross-border thing. There was a huge language barrier herein Europe.

The morning after I made a connection to the Internet with this slow, slow modem, I searched for online hotel reservations. I didn't find anything for the Netherlands but I remember I found Hilton.com in the U.S., which at that time, you could actually already make a reservation online on Hilton.com. I must admit, I did some copy-paste from them in the early stages of the project.

In Europe, people who had Internet access were university students and they don't book hotels. There were some tech companies where people had access, but it was completely different from the U.S. where in the U.S. there was AOL, which was at that time quite big already. I think in the first two years of Booking, I think 60 to 70 percent of all reservations came from the U.S. people traveling to Amsterdam or to Europe.

Well, it was just me so I needed to learn how to build a website. I wrote a business plan because I needed some money, very little, but I wrote a business plan and I sent it to everyone I knew had an email address. There were 51 of them. Also, because they had an email address so at least they knew something about the Internet. Most of them probably never visited the website at that time. It was just friends. Yeah, the total investment was 50,000 Euros. There were 18 shareholders. It was a small amount of money. I think there were even some who didn't even look at the business plan, they said, 'OK, let's do it.'

Bookings.nl Goes Live With 10 Hotels in January 1997

Bruinsma: I made a nice brochure, printed it on paper and put it in an envelope with a registration form and sent it around [to hotels]. I never visited one, just sent it around. I had a list of 2,000 hotels in the Netherlands to start with. At the time I had 10 hotels signed up when the website went live. I started with five percent commission. Hotels considered it a new market. You always have the first hotels who say, 'I'll give it a try.' That was more or less the contract, Give it a try. No contracts or a very basic one, no price deals, the hotels had to set their own rates on the website.

I had very little knowledge about the whole industry. I was a night porter in a hotel as a student. It was a good time. It gave me some inspiration and at least I knew how I the reservation process went because we got people in at night who didn't book and so they came in for a reservation. I had no clue about commission rates; that's why I started with five percent. I had no clue about room rates, about how the whole industry worked. To me, it sounded very logical that hotels themselves, they should know the best room rate they can charge at anytime. From the beginning, it was the hotel that decides about the rate on the website. I know that in the beginning there was no credit card guarantee, you just made a reservation. But, I think after the first – after two or three – reservations, hotels started to ask about credit card guarantees so we added that one as well. Up until a couple of years ago we were never involved in payments.

The Challenge of Discovery

Bruinsma: I wanted to put an advertisement in the Telegraaf, which was the biggest newspaper at that time. I got a phone call that they refused my advertisement because they talked about it and they decided not to accept any advertisements with an Internet address and there had to be a phone number.

This is '97. I think the day after when I had to come up with new ideas I started looking at search engines and what we call now Search Engine Optimization. I was pretty successful in that. I think 60 percent came from Alta Vista and we had some local Dutch ones, some national ones. They're all gone, but Alta Vista and Yahoo was not a search engine, it was still an index. You could go through it and you could click through travel the Netherlands. But AltaVista was the main supplier of visitors.

I got a phone call that they refused my advertisement because they talked about it and they decided not to accept any advertisements with an Internet address and there had to be a phone number.

Bruinsma: The second step was affiliates. My ultimate goal was to be number one if people were looking for hotels in Amsterdam because that was most of the business. I remember there were two websites about Amsterdam, about hotels in Amsterdam, which were number one and two, and I was number three. I couldn't get rid of them. I also realized that they had no online reservation system; it was an email form. I could see there was a lot of manual stuff behind it. The other one was just advertising, asking 20, 25 Euros a month to have an advertisement on the website. I sent an email to both owners and I proposed to them, 'Let's say, if I put my hotels behind your website and we split commission 50/50. How does it sound?' I think within an hour they both replied like, 'Wow, this is a great idea.' It was Channels.nl, which is still live, and the Amsterdam Hotel Guide. It doesn't exist anymore. It took about two days to program it and I remember after two days they put it live. I know two of those guys from the Amsterdam Hotel Guide. For years they haven't done anything. It was so successful from the beginning that they didn't have to do anything. They were just looking at statistics all day long, how many bookings they got.

That was a big step because it was scalable. Every day we were adding new affiliates. This was in '97, beginning of '98, I guess. Search Engine Optimization was number one. We had landing pages before the term landing page existed. I didn't know it was called affiliates. We had a system in place and then only a year or so later we heard it was about affiliates. But that was the second big growth path. This was all before Google. After two years, business was going so well that I could hire someone. At the end of '98 there were the two of us.

A Supermodel, a Tiny Dog and How Priceline Turned William Shatner Into a Legendary Pitchman

After his roles as Captain Kirk in Star Trek in the 1960s and T.J. Hooker in the 1980s, actor William Shatner's career was seemingly in its latter stages in 1998 when a Priceline.com marketing executive, Jord Poster, figured out a way to contact him through a personal connection, and helped create the magic that became Shatner as the legendary spokesman of Priceline.

Skipping the go-betweens, Poster arranged a meeting between Shatner and Priceline.com founder and then-CEO Jay Walker. Shatner signed on to do radio for Priceline and then about a year later, in 1999, Walker recalls, Shatner sent a representative in a limousine to Priceline.com headquarters in Norwalk, Connecticut, to perform due diligence on the idea of doing TV for the online travel agency.

Jay Walker: Jord Poster is the guy who made William Shatner possible at Priceline. Without Jord Poster, there would have been no William Shatner at Priceline, and without William Shatner at Priceline, I think it would have been quite awhile before anybody created a celebrity superstar brand effort. Because Jord was a brand guy. In those days of the Internet, there was nobody who hired celebrity brands, and there was nobody who did advertising on radio and television for Internet brands, for e-commerce brands. There was nobody doing that.

Jord was ultimately the guy who persuaded Bill to do this and ultimately persuaded Bill to continue to do it when he moved from radio to television, which Bill was very reluctant to do. He was on his horse on his farm, and Jord went down to the farm [in 1999]. He literally had to get Bill Shatner off the horse because he was pretty much retired and done. His career was pretty much finished at the time. So Bill Shatner's whole second career is because of Jord Poster.

What was interesting is there were two guys at Priceline. Jord Poster was the brand guy. He was all things brand. In fact, he's the reason not only that we hired Shatner; he's the reason we hired Hill Holiday, which was the agency that took Shatner, and we were catapulted. Hill Holiday was a phenomenal creative agency. Paul Breitenbach (CMO of Priceline.com 1996-2000) was the direct marketing guy, the real day-in, day-out, build the business, drive the direct response guy. So I had this team, and they never got along.

On one side is this brand guy who wants big branding efforts and wants to run full page newspaper ads where you barely even mention the name of the company; big pictures of Shatner. There's this whole idea that this is a cool and you actually can buy things on the Internet. That was one of the big, funny Shatner stories.

On the other side, you've got Paul Breitenbach, who was the consummate direct marketer, who figured out how to get radio space for pennies on the dollar and newspaper remnant space for pennies on the dollar by persuading newspapers and radio stations that we were a telemarketing company because we had an 800 number. We bought it as a direct marketing. We were in the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and we were the largest radio advertiser in Amercica for two straight years on our launch because Breitenbach persuaded the radio and newspaper guys that we were a direct response advertiser, and direct response advertisers get completely different rates. They had no idea what an Internet company was so Breitenbach persuaded them we were a direct response advertiser.

Poster, on the other hand, wanted nothing to do with direct response. He was a brand marketer. His ex-wife was a college roommate of Shatner's late wife.

Skift: This is Jord's ex-wife?

Walker: Jord's ex-wife. Jord's not alive, but his ex-wife at the time. He's been divorced. His ex-wife at the time was the college roommate of Shatner's wife, Shatner's second wife, I think. It was the only way we could bypass the agents, because when we went to try and get Bill Cosby, who was our first choice. Cosby's agents wouldn't let us anywhere near Cosby, and they wanted a fortune.

We said, ‘This isn't going to work here.’ Our choices were Shatner and James Earl Jones because we wanted great radio voices. Literally, Poster said, ‘Hey, my wife went to school with Shatner's wife, we can reach out through Shatner's wife, and we'll get you a meeting, Jay, with Shatner. We won't tell him what it's about. We'll just get you to meet with Shatner and tell him that you're working on some interesting business thing.’

When I met with Shatner and laid out the business, Shatner had no idea you could do commerce on the Internet. He wasn't an Internet user, not whatsoever, and he had no idea you could buy things on the Internet. ‘You can buy things on the Internet?’ He goes, ‘Well, Jay, are people really going to buy travel, airline tickets, on the Internet?’ I said, ‘Yes, Bill, they really are going to do it.’ It's a very funny story. Shatner says, ‘OK, I'm going to have my people do some diligence on this if that's OK with you, Jay.’ I said, ‘Actually, Jord will handle it.’

The day that Shatner's due diligence people were supposed to show up at Priceline, we had everything ready. We had the data center all cleaned up. We thought they were coming to do a technology due diligence at Priceline and Jord was all ready. Jord handled it all. This giant stretch limousine pulls up, and the guy opens the door, and a little dog gets handed out of the stretch limousine. This little lap dog. Jord was right there getting ready to say hello to whomever. Jord takes the lapdog, and then this woman's leg comes out of the limousine, and this incredibly tall, beautiful bombshell steps out of the limousine. No Shatner, just her.

And she says, ‘Bill Shatner has sent me here to do diligence on what you guys are doing.’ And Jord, without missing a beat, goes, ‘Absolutely, we're happy to have you here.’ Jord takes her by the arm and walks her into the offices, walks right past the data center, pays no attention to the data center, sits her down in a conference room, orders all kinds of food and drink, which he had setup, and then just proceeds to gently tell her stories about the people -- nothing to do with the business whatsoever -- the people and what's going on in the world, and advertising agencies, and how this would be Bill Shatner coming back, and all kinds of ways to be recognized. It was never about the business.

About an hour-and-a-half later, she was completely done. Jord held out his arm. They went out arm and arm back to the limousine, and getting into the car, she said, ‘I will tell Bill everything here is just as I expected.’

Skift: Who was she?

Walker: I have no idea, no idea. Only Jord would know who she was, and he's not alive. Literally, Bill Shatner sent a supermodel to do diligence on the business.

Skift: Why was Shatner initially reluctant to do TV?

Walker: Shatner's thing was, ‘Guys, people watching television aren't going to be buying on the Internet. They're not going to be buying on the Internet.’ In fact, Shatner, at one point during one of the meetings -- I remember hearing about it because I wasn't there -- Shatner was on the set with Jord, and they're filming. This guy has this guitar, and they're sort of playing this Firebird imitation thing with Shatner's album. At one point, Shatner sort of gets crazy, and he rips the guitar away from the guy who's playing it, and he smashes it like one of those rock stars on the ground, just smashes it on the set. Then he turns on the camera because they didn't even have a line yet, he turns to the camera and says, ‘If saving money is wrong, I don't want to be right.’ It was just complete genius, right? That's what Shatner says. And Jord has the presence of mind to say, ‘Perfect, we'll take it.’ The whole campaign was built around that.

Literally, Bill Shatner sent a supermodel to do diligence on the business.

It was just completely outrageous. It was like the inmates running the asylum. They were creating these ads that had nothing to do with airline tickets. It just had everything to do with the celebrity culture of television and how to create a brand that was different, exciting, and stood out to the point where the brand became what it is today, a real, locally known brand. It's Jord Poster who did it, whereas Breitenbach is the guy who drove the sales. Breitenbach was the guy who converted that brand into real money.

Jord is some of the genius behind Shatner and all the brand building, and Breitenbach is the genius behind radio and newspaper and direct-response advertising, allowing us to do extraordinary amounts of advertising very efficiently, which then turned out to be how we drove in the revenue. Brand advertising is great, but it ultimately doesn't ring the cash register until you drive business. Breitenbach drove the business. He was with the company for many years.

Jeffery Boyd, who was Priceline.com's general counsel and subsequently became COO and chairman and CEO of the Priceline Group: So the original credit for Mr. Shatner goes to Jay Walker. There are a lot of people running around saying it was their idea to bring Mr. Shatner to Priceline, before my time. But I think Jay gets the credit for the insight of using a spokesperson and selection of Mr. Shatner, who has a great voice, which initially was a radio campaign. It was recognizable, and because of his association to Star Trek, it could represent something futuristic. So it was an inspired choice and Mr. Shatner has been an incredible partner for Priceline. We've done a lot of different ads. A lot of different roles that he's played. He really delivered for us. He's always been a gentleman and over the years our agency gives us copy and story boards, and when they take him out to shoot, almost every time he comes back with something that's a little bit different that Bill put into the mix that really improved the ads. He's terrific.

Chapter 2: Dealmaking and IPOs

There is a frenzy of activity, creativity and acquisitions in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Priceline.com's Name Your Own Price is taking off, and warrants that Delta gets in exchange for its participation skyrocket and rival the market cap of the airline itself. Major U.S. airlines decide they want to control distribution of flights and get a piece of the action. In the beginning, without the participation of American Airlines, which owned Travelocity, four major carriers create Orbitz, which powered by ITA Software, revolutionizes how consumers search for fares. And led by the Texas Pacific Group, a bunch of other airlines —with the notable exception of Priceline-friendly Delta, create Hotwire to rival Priceline.

Booking Gets Real, and Really Competitive

Diener: I kept expanding [the HRN website] and in October of 1997, which we considered the industrial revolution of the Internet, the Internet became interactive. We were on the IBM mid-frame system. In October is when the technology was released that made the Internet interactive which means someone communicating with us could get an instant confirmation of their hotel booking. That was huge. That almost instantly doubled to tripled our business. In 1997 we were still fairly small, I'd have to look at the revenues at the time. We're talking fairly small numbers. It was in the tens of millions of dollars, not hundreds of millions, I believe.

Every hotel we approached loved it because it was new technology, it was a new source of business. The way we negotiated with hotels they were more than happy to give a better rate for this channel because it was a new channel. The expenses were less because we didn't need call centers; the cost of processing the transaction was a fraction.

Expedia and Travelocity did not negotiate their own hotel deals, they just took what was in the GDS system. We negotiated a deal with Travelocity where we became their source of hotel rooms and we ran the hotel program for Travelocity on a private-label basis using their UI. We were the back end for Travelocity. Remember when they had better values on hotels? People eventually started to realize that there's a lot of hotels, it's a big industry, it's a profit source, and so they started to do it like that. There was a company called Travelscape, which was just doing business in Las Vegas on a model similar to ours. Expedia ended up buying that company. Through that purchase, that was [Expedia's] gateway into the merchant model.

Expedia's executive team on the cover of Travel Agent magazine in 1999

Barton: Priceline was just turning from kind of a glint in Jay Walker's eye into a reality with what I would call an interesting, gimmicky, Name Your Own Price thing, which was interesting for sure, but we never took it all that seriously because we thought it was probably rather market-limited.

That's how it stacked up initially. Expedia really began to pull ahead once we started becoming a marketing spender and once we shipped this new Best Fare Search, this new faring technology, which enabled users to shop for the first time, they could shop price, and schedule at the same time. Not only did we pass Travelocity, we started to really lap them.

Walker: As soon as Priceline launched, Expedia copied, at the time, our Name Your Own Price service and put it up on their site.

We sort of said, 'You can't do that guys.' We had patented the business process of securing a unit of demand with a credit card for an irrevocable offer and eventually we settled and then they stopped doing it, but they never thought it was going to be very big anyway.

The New Competitors

Karl Peterson, founding CEO of Hotwire

Karl Peterson, who was founding CEO of Hotwire and currently is a Sabre board member and managing partner and head of Europe for TPG: I joined Texas Pacific Group (TPG) in 1995. I was working in the early days of private equity, and we were always doing things off the beaten path, which was one of our themes or investment strategies. We came up with the idea of starting an online business with a bunch of industry partners because we thought they had all the entrepreneurial spirit of two kids in a garage. It was interesting. But, given the fact that we knew a bunch of big corporates, we could bring a team of investors and corporate partners together to have an advantage over the two guys in a garage, but that we would run it independently.

We went around to a bunch of different players in different industries, and because of what my founders at TPG had done first with Continental Airlines, taking it out of bankruptcy, and then America West not too long after, we had a pretty good understanding of how airlines worked. We had a pretty good understanding of this anomaly in the marketplace, which was Priceline.com. It had given a huge stake in the business to Delta and negligible, if any stakes,to anybody else.

At one point in time, Delta's ownership of Priceline was worth more than the airline itself so we used that strange phenomenon to rally the rest of the industry together to create Hotwire.

You know Larry Kellner was at the time chief financial officer, I believe, and maybe becoming chief operating officer of Continental. They're thinking was you've got Expedia and Travelocity doing all of the traditional retail distribution online, and Orbitz was going to play there and to make sure that supplier power becomes great. Although, now it's ironic that they're all owned by the same enterprise [Expedia Inc.] Again, at one point in time the airlines wanted a big piece of Expedia.

At one point in time, Delta's ownership of Priceline was worth more than the airline itself.

They called it T2, the Travelocity Terminator, which was Orbitz. It was the same business model, but just with a lower-cost distribution scheme, which made it a little bit harder to get the customer acquisition right. When you gave your own business [Orbitz] a tougher starting hand, which is how much you're going to make per transaction, they had to do smart things but it got a lot of traction.

Hotwire was the analog saying, well, if Orbitz is to be the Expedia or Travelocity rival, Hotwire is to be the Priceline rival. It was just a different class of inventory, the deep, distressed inventory that had to be sold in a very different way to allow the traditional retail pricing channel to be less effective. The opaque channel [Hotwire and Priceline] is what we all called it. Back then, pre-9/11, the airlines had structurally much greater excess capacity than they do today, and the way that they could optimize the revenue management was to sell a few more seats on all these flights by using the opaque channel.

It was the combination of the airlines wanting to get an investment in the [distressed inventory] channel, and they were not going to get it from Priceline. Remember, Priceline made it's living – pre-Booking.com – on this pricing gimmick of you tell me what you want to pay and after you've figured that out, I'll tell you whether or not that works or not. For a while it took a long time to respond. We used to say that there was the triple whammy. If you had to do the research, you didn't know whether or not you were going to get it [the reservation] once you did the research. And then oftentimes if you did it, you probably paid more than the minimum price … With the help of the airlines, we came up with a model that said we'll just tell you the price that we're willing to offer you for this. As a result, we were able to catch Priceline on air volumes relatively quickly with a fraction of their marketing spend.

Priceline.com's Breakthrough With Delta